WF: Do building and the use of buildings also flow into such scenarios?

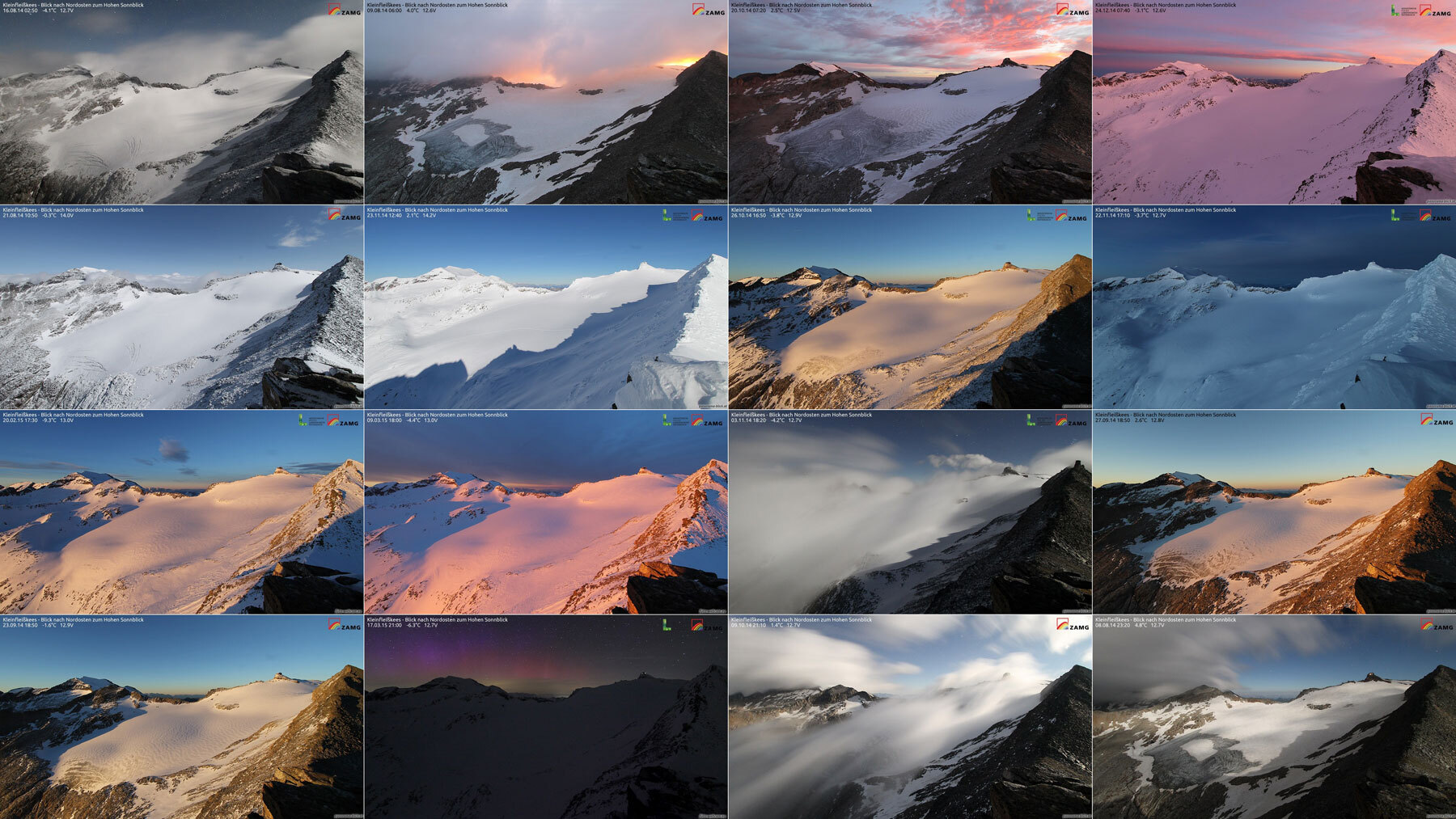

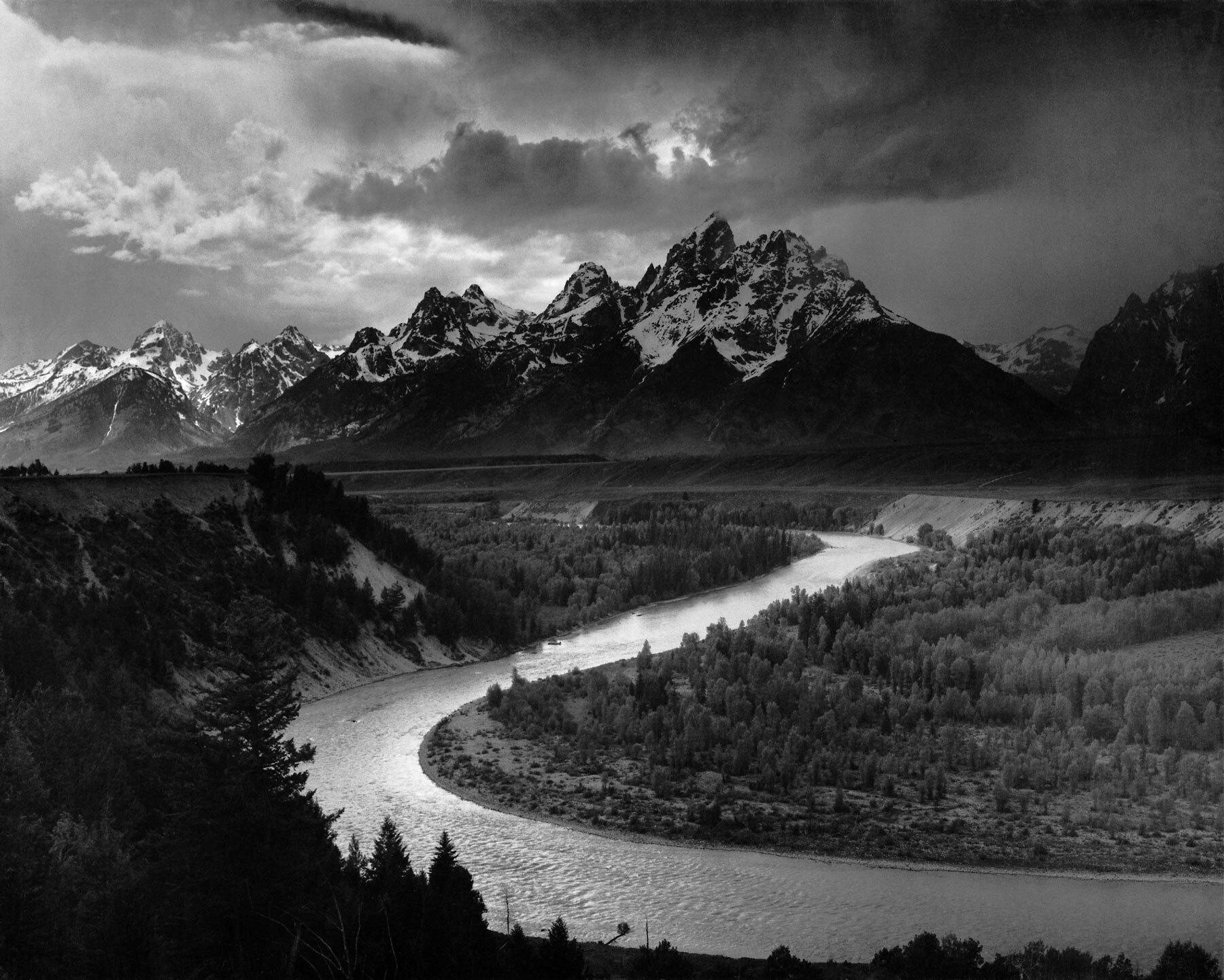

MO: We've known for a long time that urban areas as such are becoming warmer because they contain more hard surfaces, which absorb more solar radiation during the day that is only released more slowly during the night. Special high-resolution models enable us to study the impact of, for example, the development of urban spaces. We can input individual alterations into these scenarios, such as changes in the landscape design or painting things white: This enables us to ask, how does this impact upon the space?

WF: Can you briefly explain to us which types of data you can turn to in order to perform these calculations?

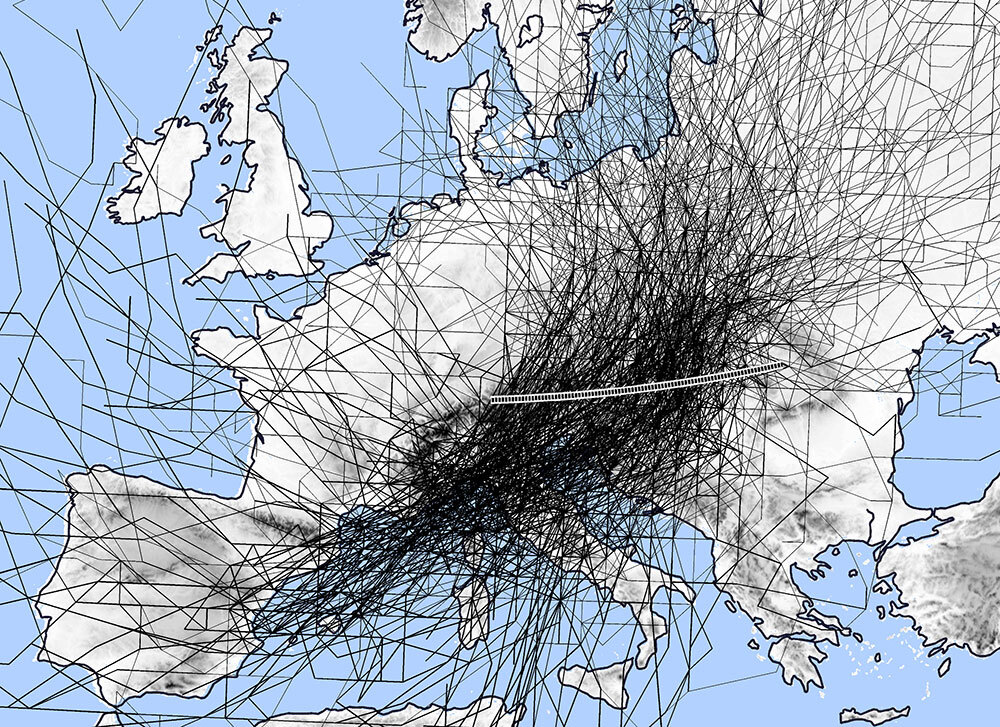

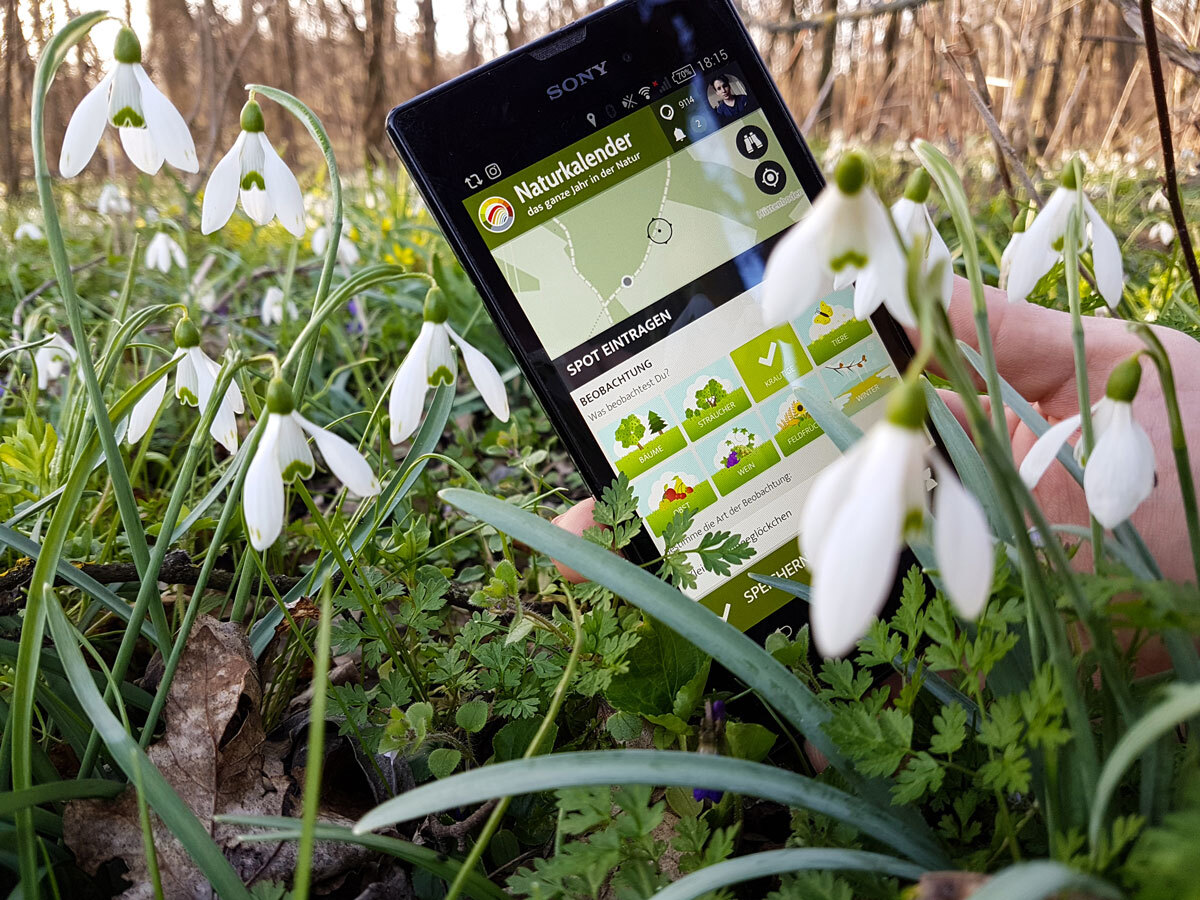

MO: In the case of urban spaces we work with ultra-high resolution airborne laser scans, where small-scale effects such as shade or the channelling of wind fields through gaps between buildings can interact with one another. We are already able to achieve resolutions below the one metre range, as a result of which small-scale scenarios such as sunlit streets surrounded by high buildings vs. shaded side streets can really be broken down so that we can relatively realistically model the effects of local energy production. Of course the resolution of satellite data is also constantly increasing but we are still significantly below where we want to be. Drones also now permit us to record meteorological effects in tiny areas and to see how temperatures and humidity levels change in line with other parameters. Taken together with the other data, this opens up completely new possibilities.

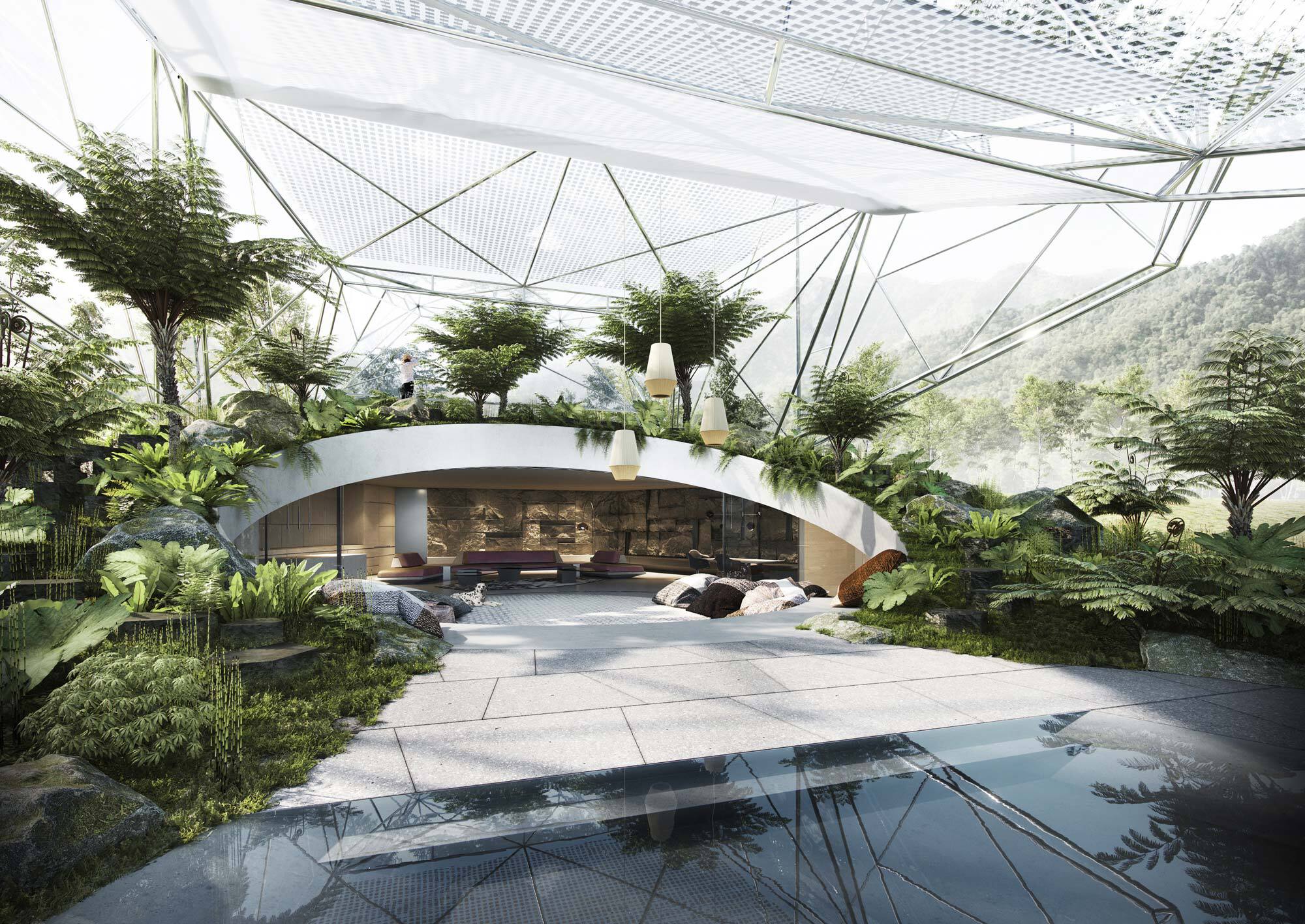

WF: On the basis of both the investigation of existing urban situations and the data that is generated, would it be possible to influence the design process of architecture, so that architects can assess the consequences of their decisions upon, for example, the microclimate in advance?

MO: This is already happening in some cities. It's not enough to do this at the level of an individual block but, rather, one has to include the entire urban planning process. Some cities also already have urban climatologists, who apply their expert meteorological knowledge to the building process. But I believe that much more can be done in this direction. It just needs more drive.