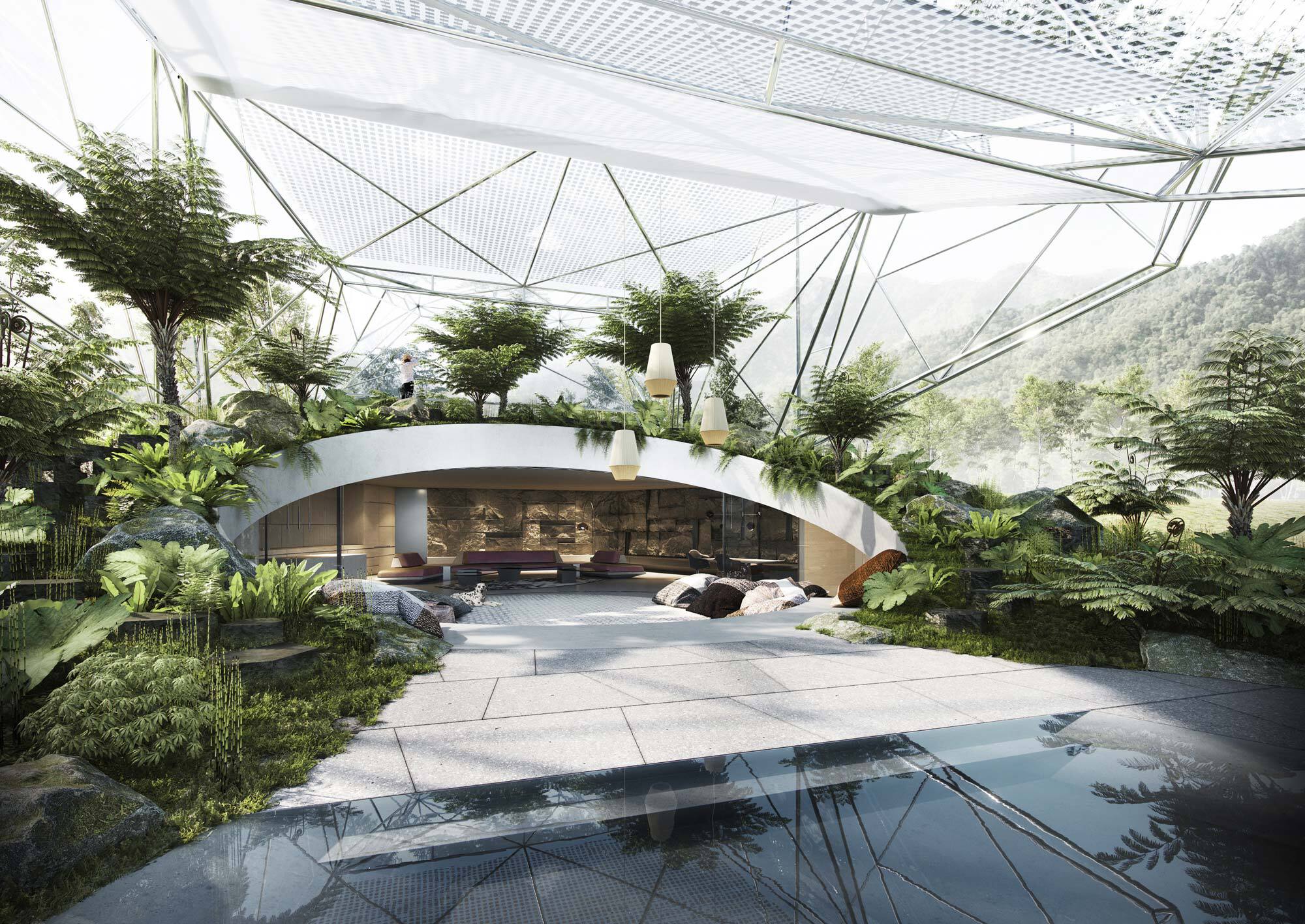

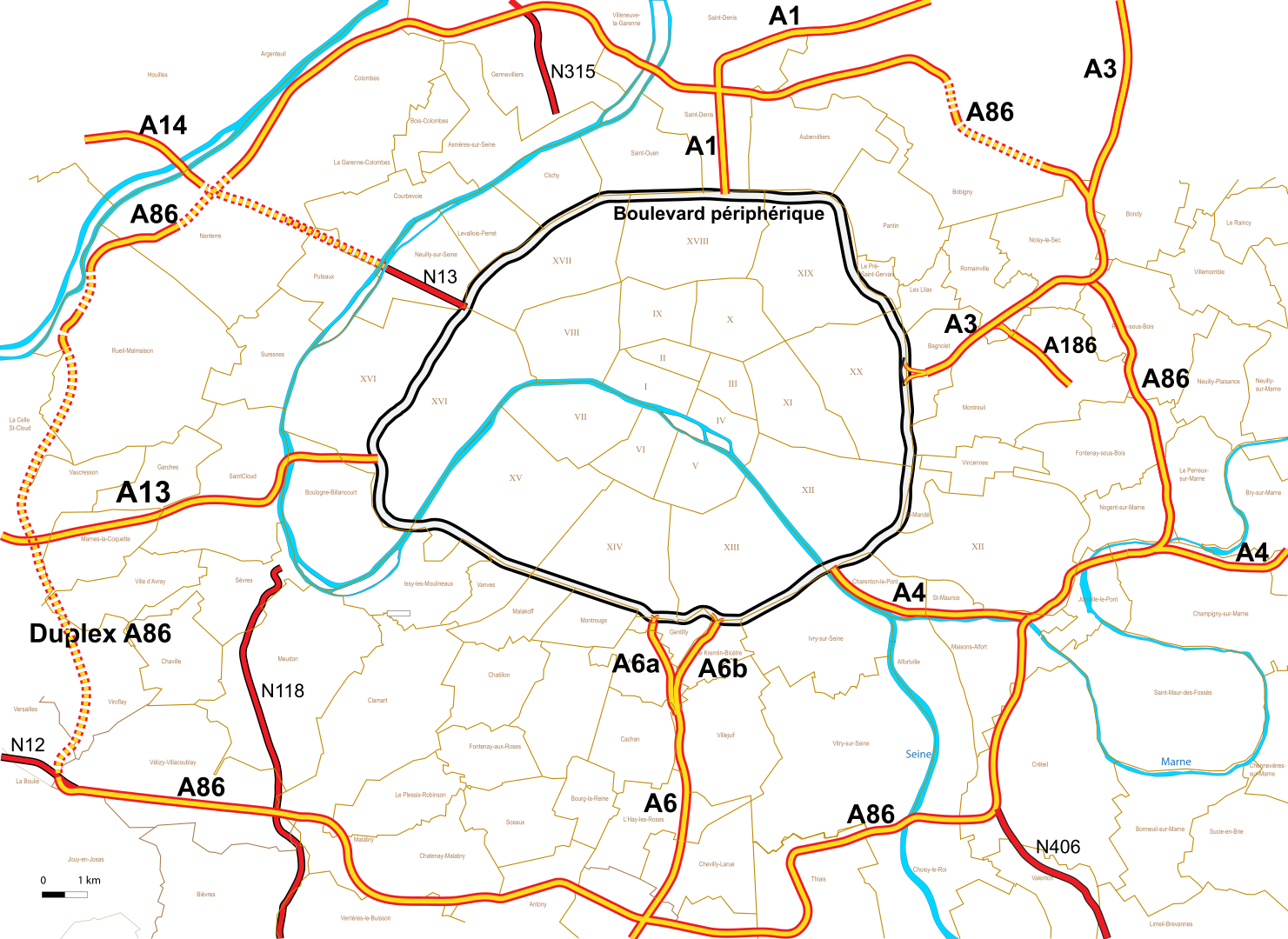

The current transformation of our idea of nature is tangible in formal terms. Firstly, the debate about limiting the damage that has already been caused by global warming permits us to speak of a shift in global awareness. Secondly, the current pandemic has generated a global need for places of recreation that, ideally, have as much greenery as possible. Our city planners are attempting to react to this massive pressure for change, sometimes with impressive speed. Private cars, which have long been regarded as sacrosanct, are suddenly having to make way for newly created movement zones and bicycle or multipurpose routes and have become central to the debate about addressing traditional aspects of the urban way of life. The fact that, until recently, this way of life was equated in our collective consciousness with the almost total renunciation of nature is reflected in the paradigms of modern city planning, which employed the mantra of hygiene to declare war on the squalor of untamed nature. Against the background of the developments discussed above, the paradigm of concreted cleanliness, which appears, from today's perspective, to be a reductionist short circuit, is being questioned in many places and, given the scale of the looming problems, being transformed into new forms of action. For example, anyone who regarded Haussmann's intervention as unique in the annals of European city planning will have been more than a little amazed just over a year ago when the Paris mayor Anne Hidalgo presented the plan for transforming the Périphérique – the ring motorway built around Paris between 1954 and 1973 – into a green urban boulevard. Der Spiegel, for example, described the idea as “revolutionary”.

Map of boulevard périphérique

Roulex 45, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

This, admittedly, highly spectacular example may just be one of many to have recently been presented to an amazed public in a range of locations. And yet, regardless of any hurdles that these will face before they can be realised, one thing is clear: The importance of nature in the context of enclosed space is being fundamentally re-evaluated. And it is unavoidable that planners will play a leading role in this process. Whether this role will also be accepted and imbued with the necessary vision by all those affected will, of course, be determined elsewhere.

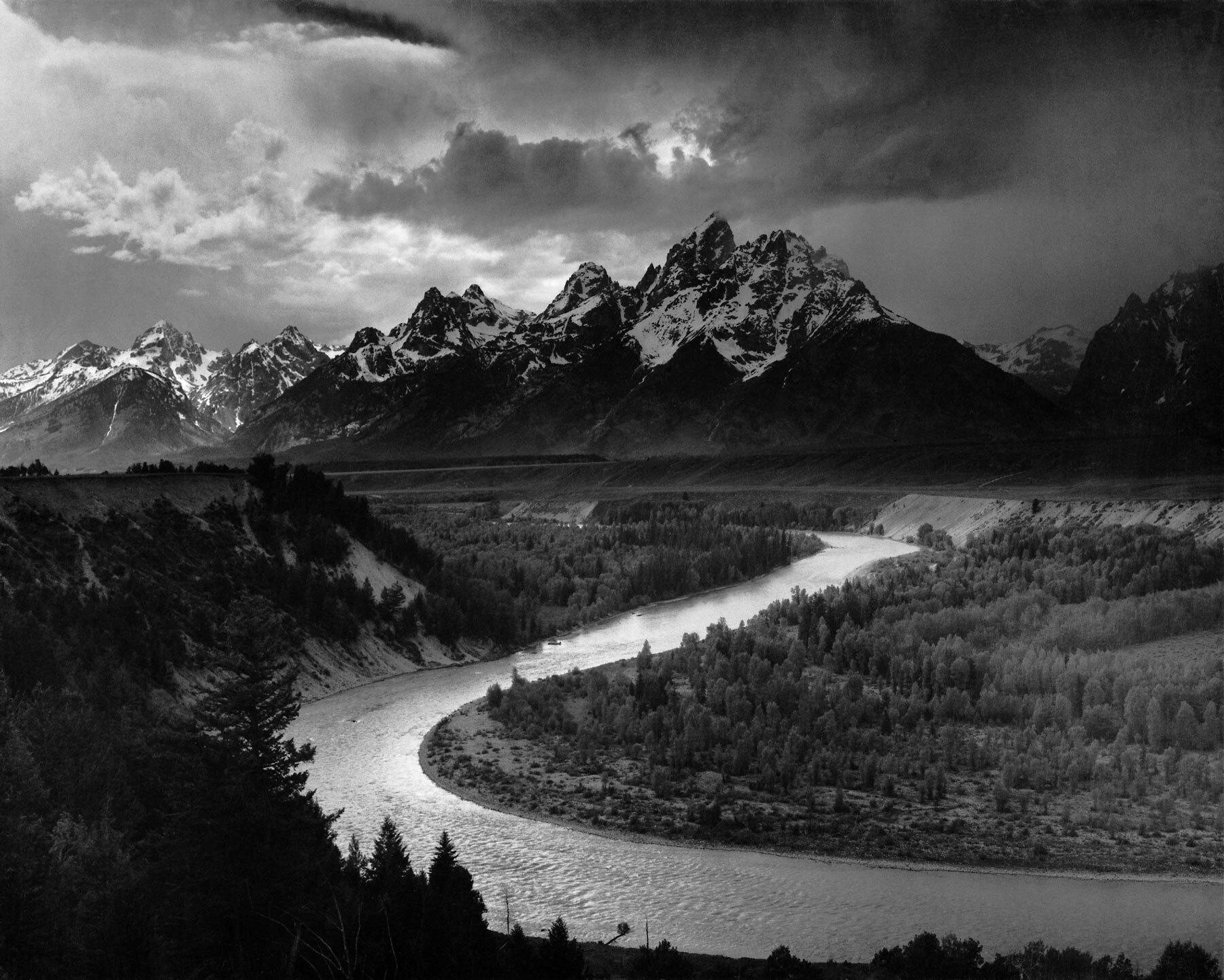

H.O.M.E. House

DMAA saw the invitation to develop the so-called H.O.M.E. House 2021 as an opportunity to investigate a number of subjects that have come to the fore in their work in recent years at the scale of the detached house as a means of also questioning the extent to which this type of building will continue to be relevant in the future.

The tradition of investigating – both implicitly and explicitly – the “House of the Future” can be traced a long way back in architectural history. Every investigation of the subject of living space revolves around the questions of whether, implicitly, current standards and conventions should be unquestioningly adopted and, hence, perpetuated or, explicitly, whether transformation or innovation should be risked in order to attempt something new and, thus, add a new facet to the “notion” of living. The avant-garde and often uncritical belief in progress of post-war modernism was particularly dismissive of the so-called context, of issues related to the concrete spatial, socio-cultural, economic or political/ideological framework of a project. In this regard, much has changed since postmodernism; particularly against the background of the debate about global climate change. All at once, the social, cultural and ecological impact of concrete building measures is being called into question, investigated and, where possible, mitigated or, ideally, eradicated completely. We are suddenly focussed on the social and cultural added value that results from or is encouraged by individual projects. Due to its scarcity, building land has suddenly become a valuable resource, which we must handle with care and use as little of as possible, both in cities and in the countryside.

Nature itself has also become a valuable and threatened resource and is no longer reduced to left-over urban sites and the private greenery of the garden of one's house in the country. Architecture has become a profession that places great importance on taking care of the recreational qualities and biodiversity of our green spaces and regards these as key quality criteria. Tiny gardens at the bases of trees and planted façades designed to cool central urban zones, expanded parks, continuous green space, the direct seepage of surface water over large areas or the use of rooftops for small city gardens are just a few examples that show how rapidly and comprehensively this “new” ecological awareness has gained ground in architecture.

IN THE “ANTHROPOCENE” AGE, NATURE, RESHAPED BY TECHNOLOGY, IS BECOMING AN INTEGRAL PART OF THE ARCHITECTURAL ASSIGNMENT.

However, what we are only just beginning to distinguish against this background is the outline of a “new” relationship with nature that has lost its innocence in this “Anthropocene” Age, as a result of which it is no longer possible to simply differentiate in line with the dual logic of “man-made” or “untouched”. The expression “Anthropocene” (from the ancient Greek ἄνθρωπος ánthropos – human – and καινός – new) is a proposed name for a new geo-chronological age: in which humans have become one of the most important influencing factors upon the Earth’s biological, geological and atmospheric processes. Nature is the result of a “technological condition” that now has to be determined. Nature, reshaped by technology, is thus becoming an integral part of the architectural assignment and can no longer be understood as a picturesque or symbolic foil to a completely autonomously designed architectural setting. This is where DMAA's proposal comes in:

House and nature become one, can no longer be truly separated and, in this form of hybrid simultaneity, are also technologically dependent upon each other. The building physics considerations regarding the heating and cooling of the building go hand in hand with the capacity of the glasshouse, which wraps itself like a green cloak around the hard core of the building structure. The precisely developed envelope makes a significant contribution to the formal significance of the house. The ancillary spaces are located in a partly buried base, which opens out via the internal circulation into a shell-shaped, covered living room that is located to the rear and smoothly merges into the greenery of the glasshouse.

House and nature become one, can no longer be truly separated and, in this form of hybrid simultaneity, are also technologically dependent upon each other.

The thermal differentiation between the individual spaces follows the principle of an old farmhouse, whose living spaces are arranged in a ring around the oven in the open kitchen in the hall as a result of which they are much warmer than the bedrooms on the floor above. The glasshouse offers, on the one hand, an enlarged living space and, on the other hand, a piece of domesticated nature, which can be shaped, used and changed in line with the wishes of the residents and within the framework of the concrete microclimatic conditions. Thereby, rather than contrasting with the organic forms of the surrounding nature, the architectural form is the designed result of a “re-naturalised” living environment, in which the specific qualities of both aspects are combined into a new symbiosis.

In this sense, the novelty of this house can be found in the uncompromising and flowing simultaneity of nature and space and in the extensive freedom with which the architecture can perform its unique role of defining the interfaces with the broader context. It is just as possible to multiply this principle horizontally or vertically as it is to find an alternative urban or rural location. Against this background, the idea of an alternative use as an urban apartment block with a communal green space comes to the fore. Hence, the ideas behind the H.O.M.E. House are also currently being applied to the development of an urban apartment building in Bremen.

Residential building with glasshouse

in Bremen

This project by DMAA, which is still under development, is an expression of the desire for the closest possible relationship with external green spaces in dense urban centres. The residential building exemplifies how this desire can be met by constructing an economically and socially compatible, collectively usable glasshouse on the roof of the building. At the same time, DMAA combines this idea of a green urban crown with the principle of circulation proposed for the building: This is a pergola, a generous space between the building and the façade, whose rich planting acts as a natural filter placed before the load-bearing structure that regulates the views of and the pollution coming from the urban surroundings.

As in the H.O.M.E. House, the thermal differentiation between the individual spaces follows the principle of an old farmhouse. Here, however, the heat extracted from the central living space in winter is used to heat the glasshouse. The expanded living space on the roof of the building offers residents the possibility to collectively shape and use their own recreation space, which will then have the potential to become an identity-shaping anchor for the community of residents. From the architectural point of view, the garden thus becomes a fixed element of the spatial development without any need for such individualised external spaces as balconies or terraces.

Conclusion

This brings us full circle to the #PlantFever that is currently raging across social media channels and expresses our desire to not only find more greenery in and around our private living spaces, but also share this with others. The history of the representation of greenery as reflected by fine art and architecture helps us to understand that this phenomenon is much older than our social media feeds and has also always achieved the outcome that we are focussing upon in this issue: The continuous modelling of the cultural conventions that govern the relationship between humans and nature.

Renderings: Toni Nachev for DMAA