MKH: So where does this trend come from? And how is it changing?

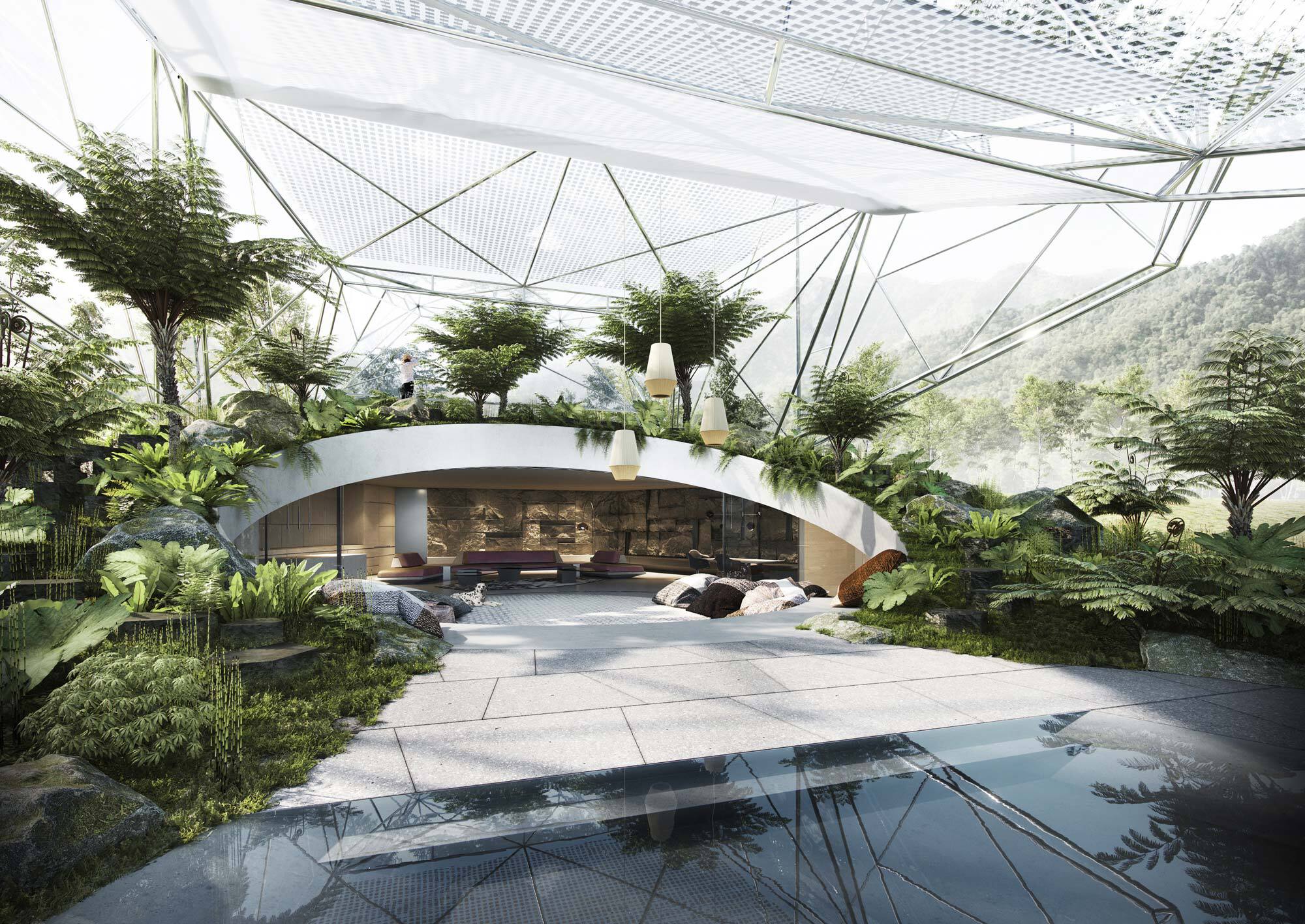

EW: It's not really so new. Over the centuries, multitudes of researchers wandered around seeking to unlock the botanical secrets of the continents. The first potted plants arrived in Europe by ship, often from the colonies, and ended up, from the Biedermeier period onwards, inside our homes. Like paintings and books, plants were presented on flower stands in salons as symbols of prosperity. In England, this led to a form of “fern fever”. Huge examples were exhibited alongside palms on specially built jardinières. The progressively better heated living rooms of large late nineteenth-century villas with their huge windows offered more and more space for such flowering plants as clivia or begonias. Not until the Bauhaus, with its architecture of full-height windows and its elimination of the strict division between indoors and outdoors, was there an attempt to render indoor plants, which were perceived as conservative, obsolete. And yet the opposite happened, because these rooms offered even better growing conditions. Since then, each decade has had its fashionable plants and now we find ourselves in an omnipresent “plant fever” – where the invitation into the living room is virtual, millefleur has been replaced by monstera and #PlantBox is the new jardinière.

MKH: What, in turn, is the impact of all this on your work? Or, put another way: Do you benefit as an artist from this broader awareness of botanical subjects?

EW: The reception has changed somewhat. As a student I was laughed at for concerning myself with something as apparently insignificant as a flower, when there were so many more radical and political issues that one could address. The interface between art and nature was long the reserve of highly contemplative Land Art. I previously saw this as avant-garde, but now I consider it to be essential. The basic subject of the botanical installation is found in ephemera. In a world in which we produce more and more stuff, I believe that experimenting with a transient medium is radical, political and poetic, in equal measure. Of course the current phenomenon contributes to a sort of popularity and yet, as an artist, I'm continuously finding that I neither belong to, nor don't belong to, a #PlantCommunity but am, rather, alone in my own garden with my thoughts.