The primary focus of this edition leads us directly to the broader subject of domesticated flora, which covers not only the historic roots of the cultivation of subtropical and tropical plants, but also landscape gardening and the large-scale growing of vegetables. Given the close connection between the way in which people, animals and living nature coexist for the purpose of producing plant- or animal-based products and the notion of the unlimited mastery of nature, this is a decisive aspect in any debate about a new ecological paradigm. The spatial manifestation of both phenomena provides the lens through which we can observe their historical development and attempt to deduce what the future may look like.

The greenhouse

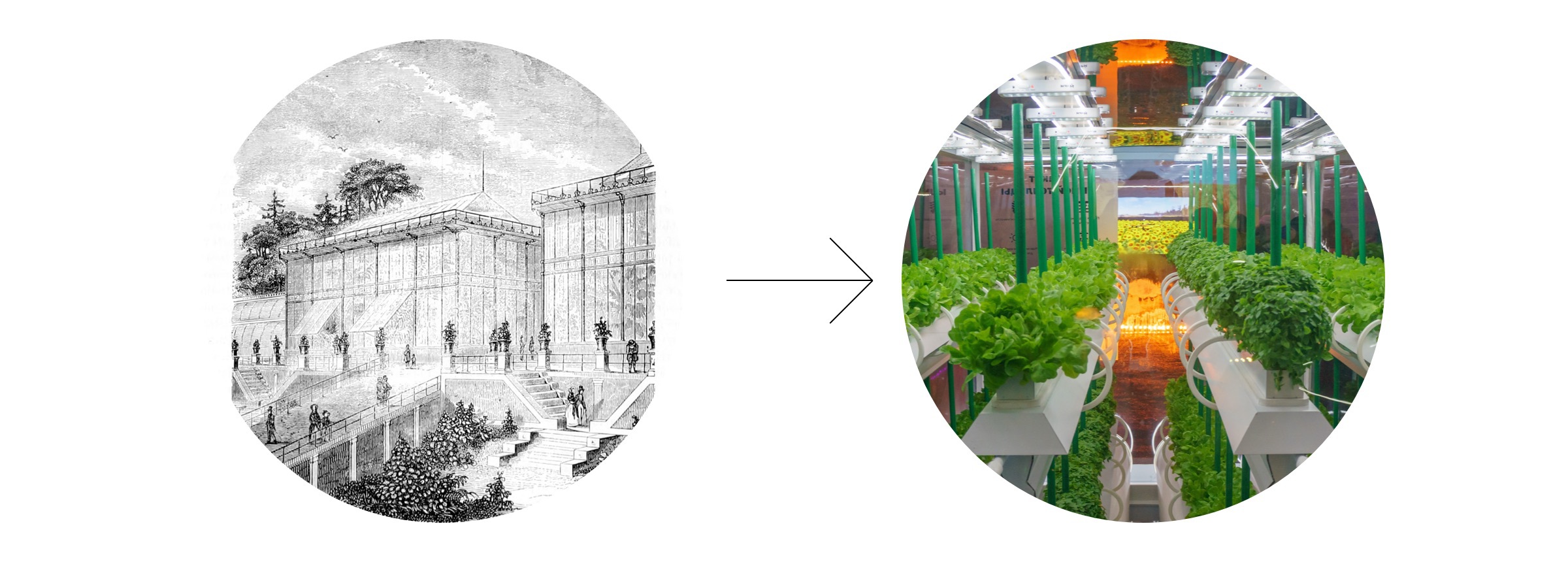

Greenhouses optimise the conditions required for growing the plants that are cultivated within them by providing a controllable and, hence, constant environment. Although the first evidence of the controlled cultivation of agricultural crops is provided by Roman sources, the best-known greenhouses are those which were built by Europe's royal courts from the 16th century onwards for the cultivation of subtropical or tropical plants and which, in many cases, have been retained to this day. Hence, alongside its representational and recreational function, the growing of “exotic” plants, with which people had to enter into a symbiotic relationship in order to merely understand what they needed in order to survive, was also connected with the progressive acquisition of botanical know-how and the resulting science, for which the greenhouses became educational laboratories.

Regarding the historical development of the accompanying architectural typology, the technical innovations of the early modern era enabled the previously extremely hermetic and strictly north-south oriented volumes to become cathedrals of steel and glass, to which the Palmenhaus in Vienna or the botanical gardens in Paris or Glasgow provide eloquent testimony. The use of the greenhouse as an element of large-scale built infrastructure for the year-round cultivation of seasonal or “exotic” varieties of fruit and vegetables first became a relevant economic factor in Europe in the 1970s. However, the role of these greenhouses, which are commonly equated with the huge complexes in Holland and Spain, as a significant cultural and spatial turning point has never received the scholarly attention essential to such a critical (in the scientifically methodical sense) aspect of the development of the countryside.

GREENHOUSES [...] first became a relevant economic factor in Europe in the 1970s.

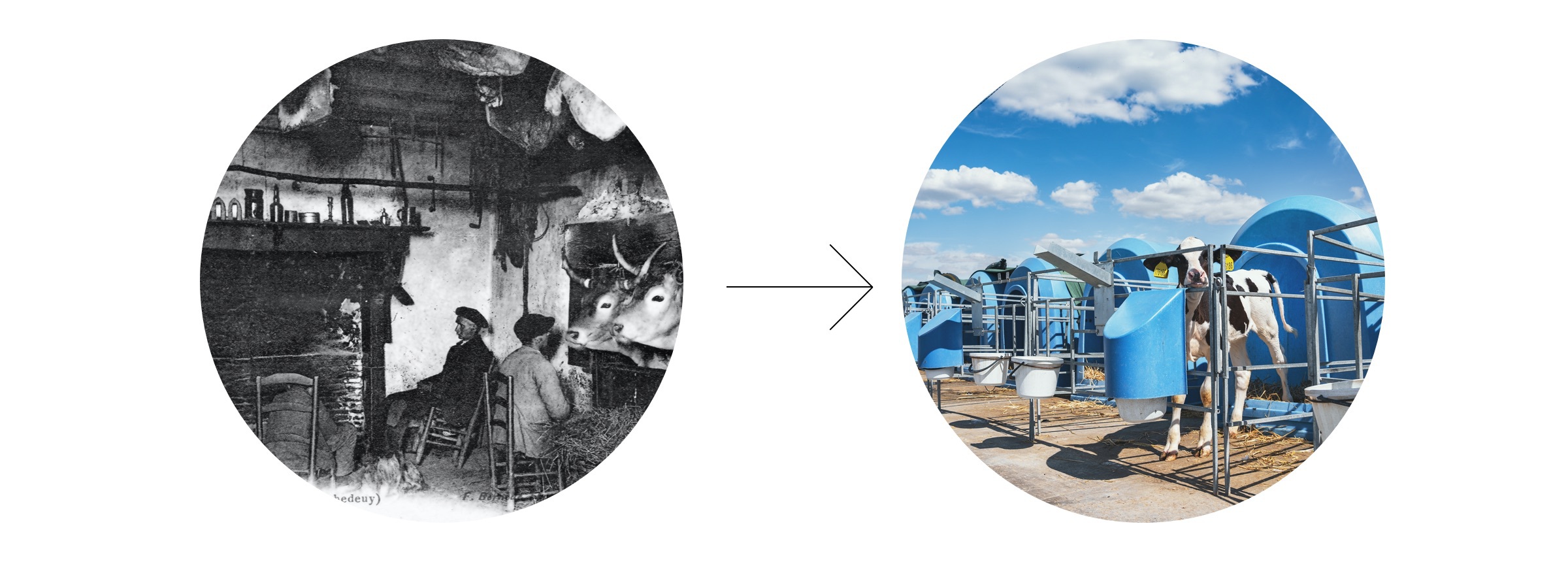

The farm

There are clear parallels with the historical development of farming and its physical manifestation. The “building type” that emerged as farmers became settled, in which living and working spaces are combined in a single block, also owes much to the idea that economic productivity can be positively influenced by the physical proximity of humans and their livestock. This romanticised image of the harmonious coexistence of people and animals continues to shape our general notion of rural life and has led to a sense of cultural alienation that is similar to the one that we have already addressed in connection with the large-scale cultivation of fruit and vegetables. Against the background of a globalised logic of exploitation, we have been offered a glimpse of an infrastructure that seeks to meet future production challenges by using the technological methods of industrial mass production. Aspirations such as regionalism, short distances and the associated ecological advantages, the idea of “small is beautiful” or good old self-sufficiency are left by the wayside.

Ecological awareness

The so-called “European Conservation Year 1970” marked the birth of the modern environmental movement, which first raised awareness of Europe’s existing environmental problems and then went on to address the issues of food production and animal welfare. This development led to the founding and establishment of numerous regional and national organic certification labels, a definition that is now protected across the EU by the so-called EG Ecological Regulation.

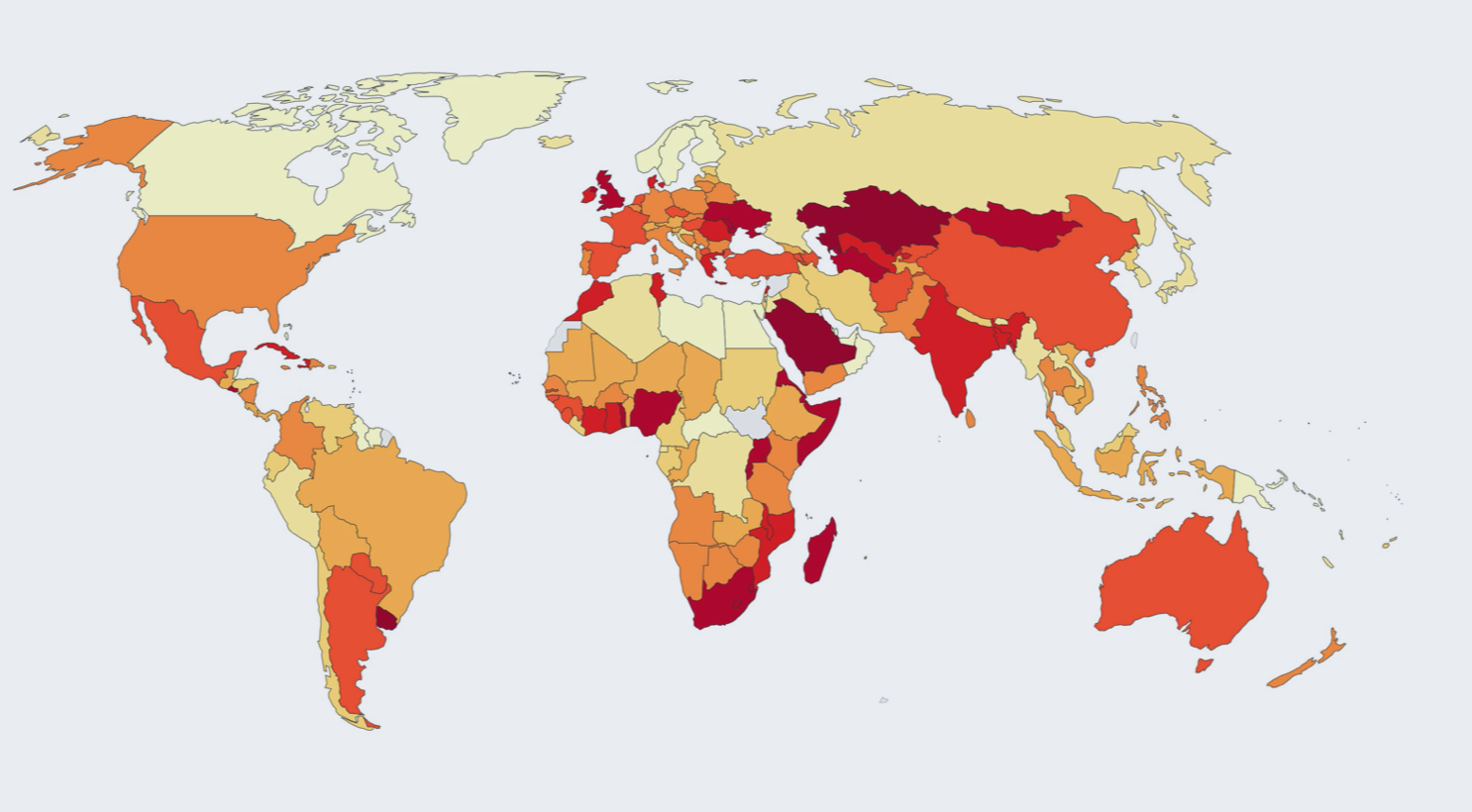

The evaluation of the question of whether the goods on offer in supermarkets with an “organic” certification can really keep the promise made by the label is just as much a subject of controversial debate as the question of whether a general shift in global food production to sustainable and ethical forms of primary agricultural production can truly deliver the harvests that we require in order to cover global needs. As it is not possible to present a comprehensive overview of the situation here we cannot even begin to examine such issues as global distribution, food losses, logistical challenges or unfertile and toxic soil.

The truth is that, in future, the countryside will probably continue to offer the largest reserves of land for the development of alternative cultivation concepts

Urban initiatives

On the other hand, we are able to present some examples which, in a number of ways, offer indications of a much more nuanced image of the future of farming than the proponents of industrialised mass production would like to suggest. Another encouraging sign comes from the fact that many new initiatives can be found in places and niches that, at first glance, suggest a mixture of the creative industries and ecological self-realisation. Many of these start at a very small scale, in the kitchens and on the balconies of apartments, in the cellars and on the roofs of cities, on the façades of buildings or former industrial sites.

What's happening in the countryside?

The concrete meaning of all this for the future of the countryside has been investigated over the course of the past five years by a team led by Rem Koolhaas and Samir Bantal and can currently be seen in the major exhibition “Countryside, The Future” in New York's Guggenheim Museum. The exhibition sheds light on the alarming absence of a broad and critical investigation of the issue of spatial development outside the major conurbations and the accompanying prolongation of the collective myth of a natural landscape that, in contrast with these urban centres, is largely unspoilt and unshaped by technology. The truth is that, in future, the countryside will probably continue to offer the largest reserves of land for the development of alternative cultivation concepts without necessarily threatening the existence of small family farms. An exceptional example of this is the South Korean cooperative for organic agricultural products Hansalim, which is the world's largest organisation in the area of solidary agriculture and whose network of over 2,000 small farmers feeds more than 1.6 million people. Thanks to its solidarity fund, the form of the organisation not only guarantees the existence of small family farms, but also increases South Korea's level of agricultural self-sufficiency to almost 80 %, which brings huge ecological advantages in terms of short distances and cold chains. It also pays close attention to knowledge transfer, which begins in early childhood and is a key requirement for a sustainable change in attitudes to the issue of food.

In any event, there are numerous signs that the necessary shift in values can occur more speedily and smoothly if it comes from consumers themselves rather than if it is left to politics or business.

The power of consumers

The example of Hasalim brings us to the final question of what each of us can contribute to a gradual transformation of the globally organised system of industrial food production into one that is based on a much smaller CO2 footprint and appropriate livestock management, that harms neither people nor animals, that respects and reinforces the planet's complex and multi-dimensional ecosystem and that offers secure prospects based on good working conditions and fair wages to all those who make their living in the sector. The fact that each individual approaches this process in a personal way was pointed out, for example, with a mixture of urgency and encouragement by Naomi Klein in her book “No Logo” in 2000. Although this book is, for good reasons, generally categorised as a critique of globalisation and gained extra attention due to its ‘favourable’ publication date just after the now legendary protests that marked the meeting of the WTO in Seattle in 1999, it essentially points out that the companies that it examines only dominate the market as a result of the consumers' own “brand mania” and that this is also a perspective that can be reversed. In any event, there are numerous signs that the necessary shift in values can occur more speedily and smoothly if it comes from consumers themselves rather than if it is left to politics or business.

And, last but not least, digitalisation presents us with new opportunities for the highly effective self-marketing of every apparently modest alternative and, in line with the motto of a small Vienna bakery “We live your dream”, for doing things that one has so far only dreamed of doing. So get started!

Footnotes

1 De re rustica (Full title: De re rustica libri duodecim “Of Husbandry: In Twelve Books”) is a comprehensive Latin guide to running a farm. It consists of 13 volumes and was written by Lucius Iunius Moderatus Columella, who probably lived in the first half of the first century A.D.

2 Opened in 1882, the Palmenhaus is the most prominent of the four plant houses in the grounds of Schönbrunn Palace and, together with Kew Gardens and the Palmenhaus in Frankfurt, one of the three largest of its kind in the world. It is home to around 4,500 plant species.

3 The Jardin des Plantes (French; English: The Garden of the Plants) is a botanical garden in Paris that covers 23.5 hectares. It is located on the south bank of the Seine in the 5th Arrondissement in the southeast of the city between the Paris mosque and “Jussieu” Faculty of Sciences.

4 The Botanic Gardens in Glasgow, Scotland is a large public park with numerous greenhouses of which Kibble Palace is the most worth seeing. The gardens were laid out in 1817 and run by the Royal Botanic Institution of Glasgow, originally to support the work of Glasgow University. The famous botanist William Hooker was Regius Professor of the Botanic Gardens in Glasgow and contributed to their development before leaving for London to become Director of Kew Gardens. The gardens were originally used for concerts and other events. In 1891 they became the responsibility of the Department of Parks and Gardens of the City of Glasgow.

5 In 1970 and 1995, the Council of Europe implemented European Conservation Years in all of its member states. European Conservation Year 1970 was the first Europe-wide environmental campaign, involved over 200,000 activities and is regarded as marking the birth of the modern environmental movement in Europe. European Conservation Year 1995 was implemented in 42 European countries and involved several thousand projects and activities.

6 Regulation (EG) No. 834/2007 (Eco Regulation)

7 Countryside, The Future is an exhibition addressing urgent environmental, political and socioeconomic issues through the lens of architect and urbanist Rem Koolhaas and Samir Bantal, Director of AMO, the think tank of the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). A unique exhibition for the Guggenheim Museum, Countryside, The Future will explore radical changes in the rural, remote and wild territories collectively identified here as “countryside,” or the 97 % of the Earth's surface not occupied by cities, with a full rotunda installation premised on original research. The project presents investigations by AMO, Koolhaas, with students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design; the Central Academy of Fine Arts, Beijing; Wageningen University, Netherlands and the University of Nairobi.