At first glance, some people will ask what Life on Mars has to do with the day-to-day challenges of the architecture business. But if we approach this question via the subject to which this edition is dedicated, the connection becomes much clearer. The investigation of ‘domesticated nature’ – in both cultural-historical terms and from the perspective of current developments, (which I will address at the end of this text) – is very closely related to the human ‘urge’ to find the ways and means that will enable us to master and, hence, control natural processes. This aspiration is embodied, for example, by the archetype of the “dwelling”, which ensures that humans remain protected from the rigours of nature. But this archetype, which initially appears to be the inversion of the paradigm of controllability, is based, on closer examination, on the same principle: the establishment of a barrier, a demarcation between an interior and an exterior, a zone of protection and control, which is structurally separated from its ‘wild’ surroundings. Besides addressing functional requirements, this demarcation or separation also has a symbolic character. The wall or façade is the visible expression of concealment, of an intimate privacy, that provides a sense of security, while everything that remains or must remain outside, is public and, therefore, exposed.

Biosphere 2, Arizona, USA

© spiritofamerica – stock.adobe.com

In the 1950s, the term “environment” entered the vocabulary of architecture and art, where it essentially describes the physical manifestation of the boundary between the inside and the outside, between the familiar and the unfamiliar (Vilém Flusser). In one decisive area, however, it goes further. This new aspect signalised the more-or-less simultaneous ‘technologisation’ of constructional developments, which promised to liberate architecture from its origins in the “primitive hut” and to lift it, in the spirit of Modernism, from the dirt and mud of the natural earth and – to paraphrase Le Corbusier – allow the assembled buildings to play in the unclouded sunlight. By doing this, the Modern Movement anticipated, to a certain extent, the developments that culminated just a few decades later in the feverish attempts to put a man on the moon and to transpose the founding myth of the United States to the “endless expanse” of space. It was against this background that an obsession with the “next frontier” became a permanent aspect of the collective fantasy of all those for whom the universe promised far more scope for discovery than their limited existence down here on earth. The sense of excess that goes hand-in-hand with this promise appears to awaken in us a collective thirst for adventure or impulse to be rebellious or reckless.

Eden Project, Cornwall, Great Britain

© peisker – stock.adobe.com

Eden Project, Cornwall, Great Britain

© Steve Mann – stock.adobe.com

Amongst other things, this has led to the creation of a whole series of cinematic heroes, who courageously ride out to face the unknown rather than comfortably settle down behind the defensive walls represented by established boundaries. The things that drag this dream of an extra-terrestrial existence back to the solid ground of reality are the apparently banal – in the wider context – human needs for oxygen, water and food, all of which are not easy to come by in the right form in the places in which these dreams are set. A recent example of a cinematographic treatment of this subject is Ridley Scott's “The Martian”, in which Matt Damon plays the astronaut Mark Watney, who has been left behind on Mars and faces the question of how he should organise the protected space of the base station in order to survive in such a ‘hostile’ environment until his hoped-for rescue. With the objective of enabling his reserves of food to last longer he transformed part of the space station into a sort of greenhouse in which he planted potatoes, which he irrigated with water that he produced himself. Something that he couldn't have achieved in the atmospheric conditions of the surface of Mars – the creation of a controlled environment that simulates conditions in which people and plants can survive for a certain period of time – had been made possible by the protective envelope of the space station. This cinematic “redeployment” recalls the experiment Biosphere 2 that took place in Arizona in the USA in the early 1990s. Here, a building complex was constructed with the objective of creating an autarkic ecosystem, which, as the name suggests, should guarantee environmental conditions similar to those on earth, while also generating information that could be evaluated and applied to the development and operation of manned bases on the moon and on Mars.

Palm house, Vienna, Austria

© michoff – stock.adobe.com

When such facilities are interpreted as greenhouses, we realise that this search for artificially created environmental conditions has predecessors in the annals of architectural history. These include the orangeries that were popular amongst the royal courts of 16th-century Europe and the structures that were used to house collections of exotic decorative and agricultural plants, above all from Asia, America and Australia, during the Colonial Era. As exhibits in the “Plant Museums” that spread rapidly across Europe and North America during the second half of the 19th century in the form of botanical gardens, the species displayed in these greenhouses were also presented as symbolising the mastery of nature. One of the best-known recent examples is the world's largest greenhouse, the Eden Project, which opened in Cornwall in England in 2001 and consists of four intersecting geodesic domes built in line with the methods of Buckminster Fuller.

Over the course of the past two decades, these structures that, up until the end of the last century, were generally built as either tourist attractions or research facilities, have become increasingly important from the perspective of both conservation and the closely-related urgent need to protect the endangered animal and plant species that we are duty bound to ‘enclose’ and make permanently accessible to a wider public against the background of global warming and the looming climatic collapse. This unusual combination of ecological awareness and didactic communication naturally continues to make use of all possible means of controlling the climate with the help of technology, ideally backed up by the corresponding parameters of the architectural form.

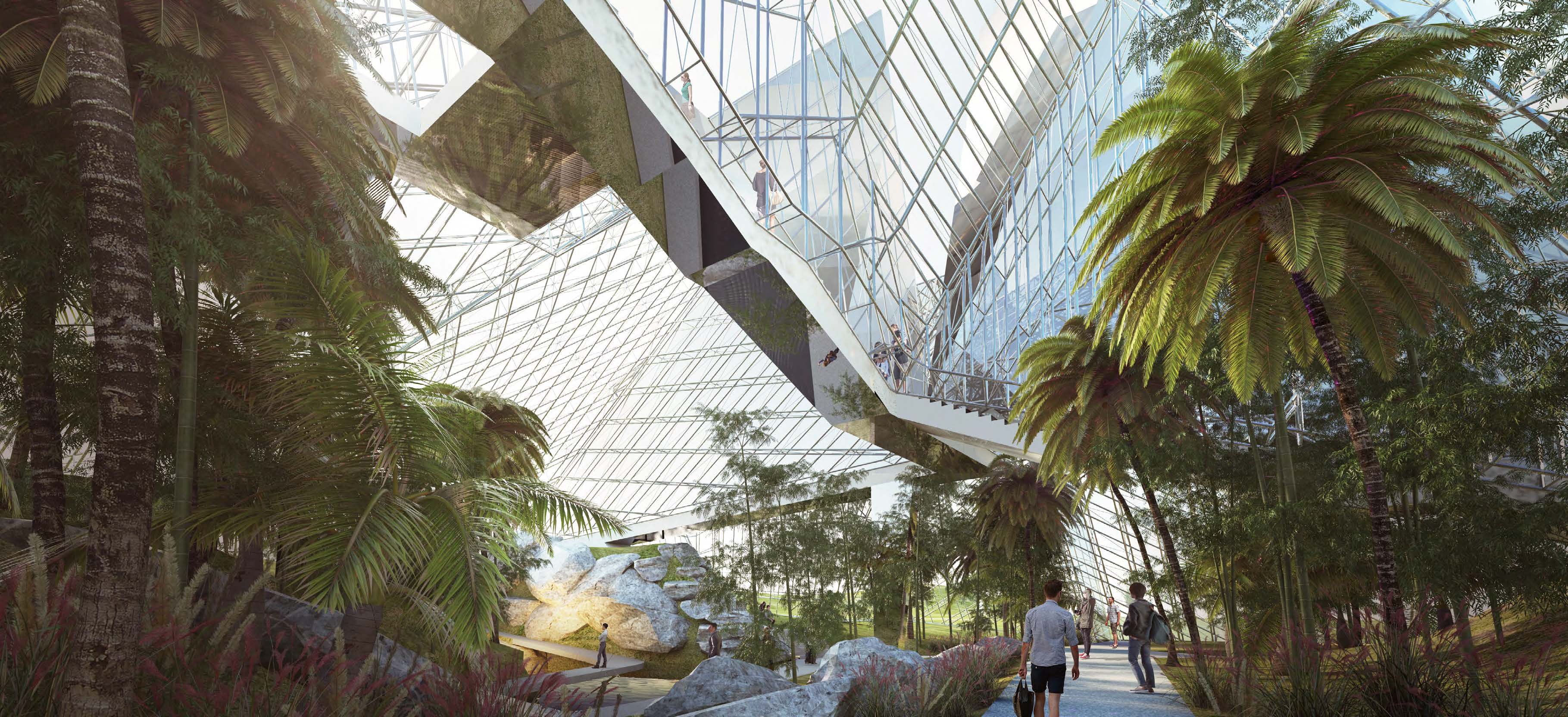

left: Expo Cultural Park Shanghai Greenhouse Garden, China, Design Development, center: Taiyuan Botanical Garden, China, Under Construction, right: Greenhouse Ganzhou, China, Design Development

all 3D-renderings © DMAA

.

A series of current projects that DMAA has developed for eco-parks, botanical gardens and greenhouses in China illustrates this idea of employing nature as a form of ‘plant-based therapeutic’ restoration of urban environments and, in this sense, as a way of researching and making targeted use of the natural capabilities of plants.

As demonstrated by the concrete case of the greenhouses in the Botanical Gardens in Taiyuan, the technological dimensions of such efforts have moved somewhat closer to the models from Mars and are beginning, for example, to hint at decisive advances in the context of the global food industry, which we will examine more closely in the next edition.

Cover image: Artistic impression of the settlement of Mars. Wikimedia Commons, NASA Ames Research Center – NASA Ames featured images, public domain